As far as the

black-and-white movies go, Kirk Douglas is one of my favorite stars. Like many of the Hollywood icons of the

classic era, he embodied toughness, grit, humor, integrity, confidence – all

the good qualities we expected to find in leading men back then. Sure, he could be a bastard if the role

called for it, but every time I see him on the screen I am hooked.

I liked him in

Kubrick’s World War I moralistic epic Paths

of Glory. I liked him as Doc Holiday

in Gunfight at the OK Corral. Superb as Vincent Van Gogh in Lust for Life. He was great in the relatively unknown Ace in the Hole. And one on my favorite Kirk Douglas

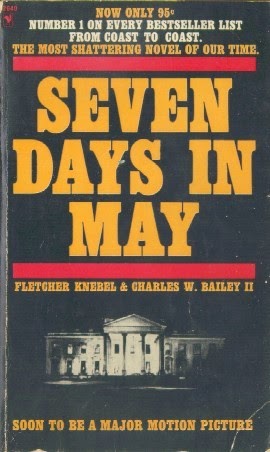

performance was in Seven Days in May,

perhaps because of the “last boy scout” aspect to his Colonel Casey, perhaps

because of the visceral power struggle with his nemesis and superior commanding

officer, Burt Lancaster, himself no slouch on the big screen.

Seven Days in May deals with a secret coup d’etat against a

flailing President of the United States (played by Fredric March), launched by

the charismatic Air Force general (Lancaster) in charge of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff. A mid-level Colonel at the

Pentagon (Douglas) stumbles across a few odd occurrences one Sunday, such as

the heads of the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marines sending in bets on the

Preakness horse race in May and the possible existence of a heretofore unknown

division of soldiers called ECOMCON (Emergency Communications Control) and a heretofore unknown military

base. Putting the pieces together in a

spooky and ominous way, Colonel Casey’s conscience forces him to bring his

uncertainties to the President. Through

some deduction and detective work, the coup is uncovered, set to take place

during a full-scale military exercise six days later. The question remains: how to stop this

exercise in brutal military muscle-flexing while remaining firmly on the side

of the Constitution and the American way of life.

Needless to say,

it’s a great political thriller with some great confrontational scenes between

March and Lancaster and Douglas and Lancaster.

One of the best closing exchanges ever in the history of movies, too.

I’ve seen it a

handful of times. Saw it with the wife

and she seemed to enjoy it too. Then I

found the novel John Frankenheimer based his movie one at one of my used book

stores a year or so ago, immediately bought it and finally got around to

reading it.

Which got me

thinking. Which was better – the book or

the movie?

The movie

generally follows the book in plot with a few major differences. In the book, the President has a few more

allies working with him; in the movie it’s just him, Casey, his chief of staff

and a senator friend. The book also

worked in more of Lancaster’s compatriots, whereas in the movie they are

faceless brass. If I recall correctly,

the movie presented March’s President, Lancaster’s General Scott, and Douglas’s

Colonel Casey as a triumvirate with more-or-less equal screen time. In the book it seemed that Casey had much

less time; his time as the focal point was given instead to the President. So in the movie if President/Casey/Scott was

at 40/40/20, in the book it’d be 60/20/20.

But that’s just an unscientific spur of the moment survey of

three-week-old memories echoing in my brain.

Anyway, the

major difference between the book and the movie is, as far as I can tell, Ava

Gardner. A character in the book who

inhabits exactly one chapter is written up for Ms. Gardner, and I can

understand why. And in the book, the

President is confronted with the option of using a tax return the Gardner

character has which has a deduction for “entertaining” General Scott, and it’s

implied this will publicly humiliate the General. In the movie it’s a stack of love letters

from a failed extramarital romance.

Maybe the first is a euphemism for the second, but either way it’s a

seedy, last-ditch fallback plan the distinguished President does not want to

use. Truth be told, in both media, it

was the weakest part for me.

The best

parts? The no-nonsense

confrontations. Between President and

potential Usurper. Between potential

Usurper and his unimpeachable underling.

Whether its March and Lancaster or Lancaster and Douglas verbally

sparring, those scenes are the payoff.

Right vs. Wrong, Right vs. Might, the Constitution – those who would

uphold it vs. those who would usurp it.

Great stuff, great dialogue. And

when it comes to the choice between reading those blistering, tension-laden

exchanges between characters on the page or icons on the silver screen, the

edge has to go with the movie every time.

And that classic

question at the end: Do you know who Judas was?

The answer is worth the price of admission.

Grade: Movie –

A+ / Book – A

No comments:

Post a Comment