© 1971 by Robert Silverberg

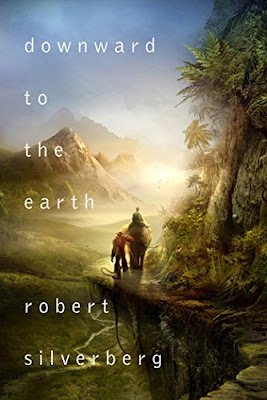

Boasting the perfect paperback length for a science

fiction novel, 180 pages, Downward to the

Earth is the best book I’ve read in 2017. Probably the best since I put

away PKD’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer

Eldritch, a book in which both share some broad themes, nearly a year ago.

That’s a long dry spell, but it was well worth the wait.

What broad themes does Silverberg’s novel dance with?

Redemption and transcendence, deep emotional needs I find within myself (though

more transcendence than redemption, but redemption’s buried down there

somewhere). Needs we all nurture and keep locked safely away. “Transcendence”

is a feature large or small in many of Silverberg’s works (I’ve read ten or twelve

of his 80+ published novels), and Downward

ends on perhaps the most blatantly literal example of transcendence I’ve

ever encountered. Such an ending might not even be publishable today.

In a quintet of words, Downward to the Earth is an: SF-stylized take on Rudyard Kipling.

The empire of Earth is in recession, and companies that have previously

governed entire alien planets have withdrawn and conceded those worlds to their

native inhabitants. Our protagonist, Edmund Gundersen, worked his way up the

chain of command to rule Belzagor fifteen years ago, back when it had the

company stamp of Holman’s World. He’s compelled to return to his old stomping

ground by a heavy tormenting conscience, for he himself stomped over the native

population in the quest to satisfy his masters at Corporate.

Belzagor is a unique world in that two sentient

species share the planet, and it’s given that each are more sentient than mankind

realized back in the good old days. The dominant denizens, the Nildoror, are

philosophical elephant-like creatures whom in the past Gundersen and his

compatriots treated no better than beasts of burden. The second race is a

species of what I think are upright sloth slash leopards. Territorial, moody,

taciturn, these creatures called the Sulidoror, seem to serve the Nildoror,

though their true relationship is not quite clear until the book’s closing

pages, a startling and unforeseen development that recalled the reveal that

climaxed Hal Clement’s Cycle of Fire.

At unspecified periods of time, the Nildoror are summoned

to make a pilgrimage to a sacred mountain in the mists of the North to

experience the “rebirth.” Disillusioned and discontented, seeking

self-forgiveness and perhaps the forgiveness of these spiritual creatures, Gundersen

asks permission to make the pilgrimage himself – and possibly undergo risky “rebirth”

– and permission is granted.

The lush world of Belzagor is a stand-in for India,

and Gundersen is a Kiplingesque figure. The novel unwinds during the

pilgrimage, alternating between deeply philosophic and troubling conversations

between the man and his Nildoror guide and flashbacks to the abuses that

occurred during Company-wide rule. An early memory is quite bizarre – the

“snake milking station” where a deranged yet undoubtedly charismatic man named

Kurtz (enjoyed that reference!) initiates a young Gundersen to the psychedelic

properties of the alien poison. I thought perhaps I ingested some myself

reading this chapter, where Kurtz warbles Hendrix-y riffs on an electric

guitar, his partner-in-crime Gio’s flute accompanying the acid rock, the snakes

drawn Cobra-like to the charmers to cede their venom, the altered states – and

the shame – that follow …

Two-thirds in, almost as an afterthought, Silverberg

spends three sparse pages detailing one of the most horrifying incidents I have

ever read – and I’ve read dozens of novels and stories by King, Koontz, Poe and

Lovecraft. It jarred me, jarred me hard, Gundersen stumbling over those two

victims at an abandoned weather station, a scene I’ll not likely ever forget.

Why did the author include it, since it does not involve main characters or

advance the plot? Probably to show that Belzagor is far from an idyllic

paradise – and that the Serpent is ever present, ever hidden in the Garden.

Gio – a relatively minor character – also suffers a

gruesome fate, but his demise is only mentioned in passing by one character to

another. Combined with the aforementioned horror, these deaths predate the

“body horror” fad in cinema begun by Alien

and which continues to this day. It’s an insider secret that good science

fiction literature predates good science fiction cinema by ten to twenty years,

and in this case the rule holds fast and true.

Well, I don’t want to reveal much else except the fact

that, after some hesitation upon learning the terrible risks associated with

“rebirth,” our protagonist decides to go forward. With equal measures of

anticipation and dread, I eagerly burned through the novel’s final pages – and

was rewarded beyond expectation. Silverberg pulls it off.

Grade: A+

Postscript:

I have decided to read through my entire backlog of

Silverberg novels this summer: Nightwings,

Tom O’Bedlam, Kingdoms of the Wall, The

Face of the Waters, The New

Springtime, Shadrach in the Furnace,

and The World Inside (the last two

purchased a day after finishing Downward

to the Earth). Waters and Springtime will be re-reads, first traversed

in the mid-90s. I am looking forward to it tremendously.

I even feel that maybe I should’ve used Robert

Silverberg instead of Philip Jose Farmer for my 2013 Exclusive Writer Reading

Project, where I spent three months reading a dozen novels and a dozen short

stories of the latter author. Maybe this will be sort of a mini-re-version of

that. More later …

No comments:

Post a Comment